Those of us who work with venomous snakes get a lot of questions about coral snakes, and we find ourselves correcting the same misunderstandings over and over again. The purpose of this post is to address some of the common myths about these colorful little snakes.

Executive Summary:

- Coral snakes are front-fanged, not rear fanged.

- Coral snakes do not have to chew to envenomate.

- The “red-on-yellow” rhyme is not 100% reliable, especially outside the US.

- Venom toxicity does not correlate very well with “dangerousness.”

- Yes, antivenom for coral snakes is back in production.

New world coral snakes

Coral snakes are members of a large family of venomous snakes called Elapidae. This is the same family that snakes like cobras, mambas and sea snakes belong to. Members of this family are called elapids, and aside from sea snakes, coral snakes are the only elapids found in the Americas, where there are more than 60 species in three genera: Micrurus, Micruroides and Leptomicrurus.

The US has only three species of coral snakes: the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius), the Texas coral snake (M. tener), and the Arizona coral snake (Micruroides euryxanthus).

Rear-fanged or front-fanged?

Short answer: Front.

A common misconception about coral snakes is that they are rear fanged, but they’re not. One of the things that coral snakes have in common with all the other elapids is that they are front-fanged snakes, just like cobras, kraits, mambas and taipans.

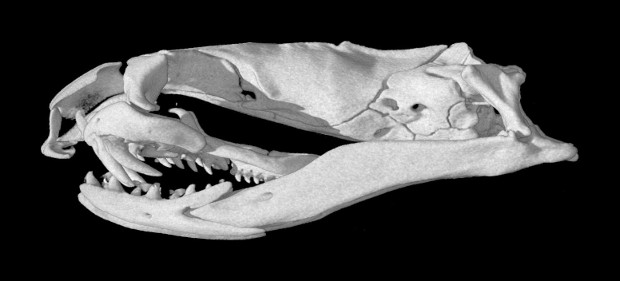

Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius) skull

Elapids are different from vipers like rattlesnakes in that their fangs don’t fold back, so they have to be pretty small to fit inside their closed mouths. In fact, coral snakes’ fangs are so small that they’re actually a little hard to see.

A common assumption is that coral snakes have to chew on you to deliver venom, but that’s not true either. This idea may have originated from the fact that coral snakes bite and hold their prey, which for most species is other snakes. This holding and chewing behavior is common among almost all snakes that eat other snakes, but it probably has more to do with not letting their prey get away than it does with needing to chew to deliver venom.

So, while it’s pretty hard to get bitten by a coral snake, they can deliver a dangerous dose of venom with just a quick bite. And while they are small snakes with small mouths, they can bite pretty much anywhere; they don’t need to get you between the fingers as you’ll sometimes hear. Any exposed skin is all they need.

Identification

Short answer: You can’t always trust the “red-on-yellow” rhyme.

Quite possibly the most misunderstood thing about coral snakes is how to identify them, and particularly how to tell them apart from harmless snakes that look similar. There’s a popular rhyme that everyone seems to know that has for decades been a popular way of telling them apart: “red-on-yellow, kill a fellow” and “red-on-black, venom lack.” There are lots of variants of those rhymes floating around, and those might not be the exact ones you’ve heard, but all of the versions have the same idea: that coral snakes can be identified by red bands touching the yellow ones.

In some places, this can be helpful in telling coral snakes apart from species like scarlet snakes and scarlet king snakes and some milk snakes. But here’s the important thing to remember: While the rule might be helpful most of the time, it’s not 100% reliable. There are some important exceptions. For example, in the Southwestern US, there’s a little nonvenomous species called a shovel-nosed snake, which has red and yellow bands together.

Sonoran Shovel-nosed Snake (Chionactis palarostris) — photo credit: Larry Jones

But that’s not the only exception. Coral snakes’ colors and patterns aren’t always typical. There are conditions like melanism — where the snake is mostly black — or albinism — where it’s lacking black pigment.

Texas coral snake (Micrurus tener; melanistic) — photo credit: Tyler Sladen

Texas coral snake (Micrurus tener; albino) — photo credit: Chris Harrison

Texas coral snake (Micrurus tener; anerythristic) — photo credit: Matthew Morris

There can be regional variations. For example, the coral snakes in the Florida Keys have little or no yellow, which might lead someone to misidentify the snake if they were relying on the old rhymes.

Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius; south Florida variant) — photo credit: Richard Bartlett

And on top of all that, sometimes there are individual coral snakes whose pattern is just abnormal — or what’s called “aberrant” — and in these cases, the rules just don’t work at all.

Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius; aberrant) — photo credit: Dave Strasser

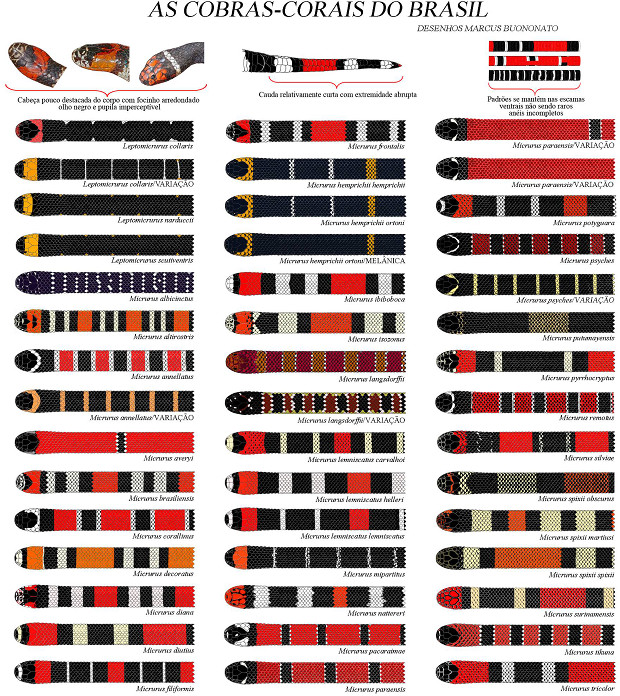

Outside the US, things get much more complicated. Throughout Latin America, there are lots of nonvenomous snakes that look like what we think of as “typical” coral snakes, including a few that have red and yellow bands together. Some of these harmless mimics are very convincing. At the same time, there are a bunch of coral snakes that don’t have the “typical” pattern.

Venomous: Red-tailed coral snake (Micrurus mipartitus), Central America — photo credit: Jörgen Fyhr

Nonvenomous: Neckband snake (Scaphiodontophis venustissimus), Costa Rica — photo credit: Kris Haas

They may have no red at all, or no yellow at all, or they may have red and black bands together, or they may have patterns that are nothing like any of these! Here are (some of) the different coral snakes just from Brazil!

Coral Snakes of Brazil — credit: Marcus Buononato

Confused? Don’t worry. There is one rule that always works, 100% of the time, and that’s this: If you’re not 150% positive about what a snake is, it’s best to just leave it alone.

Just don’t touch the snake

How dangerous are coral snakes?

Short answer: Not as scary as you think, but don’t be stupid.

I won’t tell you that coral snakes aren’t dangerous, because nearly all of them* have the potential to deliver serious — often life-threatening — envenomation. They’re not snakes you need to be messing with unnecessarily. However, they are not by any means snakes you need to be terrified of. Coral snakes bites in the US are rare (only around 100 per year, 70% of those in Florida), and unless you grab one or step on one with bare feet, your chance of ever being bitten by one is close to zero.

The US doesn’t have many snakebite fatalities. Out of roughly 6,000-8,000 venomous bites reported each year, less than one out of a thousand is fatal. (It may actually be closer to one out of every two thousand.) Of the bites from native species that are fatal, virtually all are from pitvipers, primarily rattlesnakes. I could find only two reports of fatal coral snake bites in the US since antivenom was introduced in 1967: one to a man in Florida in 2008 who did not seek treatment, and one to a five-year-old child in Texas in 1970.

So, how dangerous are coral snakes? The answer to that question is not simple, but the discussion is interesting. It is true that coral snakes’ venom is among the most toxic of all snakes in the US, when measured drop for drop. (Only tiger rattlesnakes and type-A mohave rattlesnakes have more toxic venom.) But drop-for-drop toxicity isn’t the whole picture, and in fact it’s probably not even the most important factor. While coral snakes’ venom is very toxic, they produce it in tiny quantities. An adult coral snake might deliver 10 or maybe 15 mg of venom, whereas an adult diamondback rattlesnake might deliver 300-400 mg or more.

To underscore the importance of volume, consider some examples:

- A honey bee’s venom is in roughly the same range of toxicity as some rattlesnakes.

- A yellow-jacket wasp’s venom is comparable in toxicity to a gaboon viper’s.

- A harvester ant’s venom is three times as toxic as a black mamba’s.

In all of these cases, the insect’s sting is nowhere near as dangerous as the snake’s bite, and that is because the volume of venom they deliver is so small. So while coral snakes can potentially deliver a life-threatening bite, the chance of a properly-treated bite actually being fatal is almost nil.

When it comes to the complexity of treating venomous snakebite, the volume of venom is generally a bigger factor that its toxicity. Compared to most pitviper bites, coral snake bites are generally less complicated to treat, have better outcomes, and cause fewer long-term problems.

There is another factor that works in the favor of people bitten by coral snakes, and that is the fact that their venom tends to act relatively slowly. While a pitviper bite will usually begin to manifest symptoms (pain) immediately, bites from coral snakes may not become symptomatic for several hours — often four to six hours or more — after the bite. So while all venomous snakebites are medical emergencies that must be dealt with immediately, coral snake bite patients typically have plenty of time to reach medical care before things start getting really bad.

The situation with coral snake antivenom in the US

In 2008 Pfizer stopped production of the only FDA-approved coral snake antivenom in the US. All of their existing coral snake antivenom is now long past its original expiration date. However, the FDA has tested representative batches of the antivenom each year and extended its expiration another year. So, yes, the antivenom that’s out there still works. However, that supply is dwindling. Pfizer is in the process of re-starting manufacturing of the antivenom. Additionally, there is a new coral snake antivenom from the University of Arizona undergoing clinical trials at several hospitals in Florida. It is hoped that one or both of these antivenoms will be available again by the time the existing stock expires or is exhausted. (For more about this, see “Coral Snake Antivenom” in the bonus clips of The Venom Interviews.)

Update: In October, 2016, Pfizer announced that its coral snake antivenom (formerly Wyeth’s) was back in production and available to order. Clinical trials of the new antivenom are effectively on hold for now.

* Arizona coral snakes of the genus Micruroides are tiny snakes. There are no records of fatalities for that species or, as far as I’ve been able to find, even a very serious bite from one. That said, you don’t want to be the first one, so leave them alone too.

Related Links

-

Why zoo antivenom is different from what doctors expect (Leslie Boyer, MD)

-

Emergency Treatment of Coral Snake Envenomation With Antivenom (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Questions? Comments?

Please join The Venom Interviews group on Facebook for the discussion of all professional and scientific aspects of venomous herpetology.