Snake taxonomy for masochists: Everything you never wanted to know about snake names.

If you frequent any of the growing number of snake education and identification groups on Facebook, you’re probably used to seeing conversations like this:

A: That’s just Pantherophis alleghaniensis. Nothing to worry about.

Q: Uh, okay, but what is it?

The asker and the answerer are literally speaking different languages. Scientific names may not seem to be very helpful for anyone not familiar with them, so why should anyone use them? Aren’t common names good enough? What difference does it make? Don’t people just use scientific names to look smart? (Short answer: Maybe some do, but I don’t think that’s usually the case.)

What’s the problem with common names?

Where do I even begin?

Common names don’t always tell you much about a snake. I mean, blind snake are (more or less) blind, lined snake are lined, and smooth green snakes are smooth and green, but other names, like lyre snake, queen snake, massasauga, Kirtland’s snake, and Dekay’s snake don’t tell you anything about those animals, even if you know who Jared Kirtland or James De Kay were. (Patronyms are especially unhelpful.) Forest flame snakes have nothing to do with fire-bellied snakes, and good luck figuring out what a dragon snake is. (Seriously, dragon snakes are real, and they’re really weird. They don’t know what they are.)

Common names can be confusing, if not outright misleading. Corn snakes and fox snakes are actually rat snakes; they eat rats, not foxes or corn, but not all snakes that eat rats are rat snakes. Bullsnakes have nothing to do with bulls, tiger snakes have nothing to do with tigers, but tiger rat snakes are rat snakes and they eat rats. Bird snakes eat birds, but vine snakes don’t eat vines, and wart snakes neither cause nor cure warts. And despite the abundance of snake-eating-snakes, there’s no such thing as a “snake snake” — although arguably there should be — but lots of snakes eat other snakes, so you can imagine what a mess that would be.

Milk snakes don’t drink milk, and they eat rats, but they’re not rat snakes either; they’re actually kingsnakes. Longnosed snakes look like kingsnakes, but they aren’t, and their noses really aren’t very long. Hognose snakes do have long noses, but they’re not longnosed snakes. Hognosed vipers have hog-noses, but they aren’t hognose snakes. Hognose snakes in the US (Heterodon) are sometimes called “puff adders,” but real puff adders are an African viper (Bitis arietans). There’s also a hognose snake in Africa (Leioheterodon madagascariensis), but it’s not a puff adder there either.

European adder (Vipera berus). Photo by Bernard Dupontby

The adders in Europe are completely different from death adders in Australia, which in turn are completely different from adders in Africa. Africa also has night adders, which are vipers that look like harmless colubrids, but are neither harmless nor colubrids.

Not all snakes that live in trees are tree snakes, and tree snakes don’t always live in trees. Water snakes live in and near water, but not in the sea. Not all snakes that live in the sea are sea snakes, and not all snakes that live in the water are water snakes.

In Asia it’s common for people to use the name “king cobra” for true cobras, even though true cobras aren’t king cobras, and king cobras aren’t true cobras, but since king cobras are The King, they can pretty much do whatever they want. Let’s make it worse: “King cobra” should refer to only one species (Ophiophagus hannah), but that one species probably should really be five or ten different species, but that phylogeny isn’t worked out yet. At least “false water cobras” are honest about not being real water cobras; it would still be better if people just called them Brazilian smooth snakes, but nobody calls them that.

Cape coral cobra (Aspidelaps lubricus). Photo by Ray Morgan

Coral cobras in Africa are neither coral snakes nor cobras. However, some references simply refer to all elapids as “cobras,” in which case they would be. (But they’re still not.)

Mexican burrowing pythons (Loxocemus) burrow, but they aren’t limited to Mexico, and they’re not even pythons. Bromeliad boas (Ungaliophis) — also known as “dwarf boas” — aren’t really boas.

Here in Costa Rica, the common name “mica” means whipsnake, which is used for several different long, thin snakes, including bird snakes (Phrynonax) and tiger rat snakes (Spilotes), which totally aren’t whipsnakes. (Whipsnakes in the Americas are harmless, but whipsnakes in Africa are venomous.) We also have “toboba gata” — a harmless colubrid called “lyre snake” in English — as well as “toboba chinga,” which is a slender hognose pitviper.

In many cases, snakes have popular colloquial names, which vary by region, but don’t mean much to herpetologists. “Chicken snake” may be used to refer to almost anything that hangs around chicken coops. Pygmy rattlesnakes (Sistrurus) are sometimes called “ground rattlers”, and garter snakes (Thamnophis) are often called “garden snakes” (or “gardener snakes”).

A lot of “correct” common names are too generic: In the US, “water snake” could mean anything in the genus Nerodia, “rattlesnake” may mean any snake in Crotalus or Sistrurus, and “pitviper” refers to all snakes in the subfamily Crotalinae, and there are a couple of hundred different species of those.

When you consider all the snakes in the world, it gets much worse. All of the following names refer to completely different species in different parts of the world: rat snake, cat snake (or cat-eyed snake), racer, whipsnake, garter snake, sea snake, vine snake, tree snake, green snake, brown snake, black snake, hognosed snake, coral snake, false coral snake, tiger snake, grass snake, copperhead, cobra, king cobra, asp, adder, puff adder, mussurana, cribo, harlequin snake, and undoubtedly others I’m just not thinking of right now.

Garter snakes in the US (Thamnophis) are harmless, but garter snakes in Africa (Elapsoidea) are potentially dangerous elapids. Copperheads in the US (Agkistrodon) and in Australia (Austrelaps) are both venomous, but they are not even in the same family. Brown snakes in the US (Storeria) are harmless, but brown snakes in Australia (Pseudonaja) kill people, and quickly.

![Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis). Photo by flagstaffotos [at] gmail.com](http://thevenominterviews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Brown_snake_-_victoria_australia.jpg)

Eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis). Photo by flagstaffotos [at] gmail.com

There are no species in the US that are properly called “black snakes,” but there are snakes that are black, mostly black racers (Coluber constrictor) and black rat snakes (Pantherophis obsoletus), but black rat snakes are no longer called black rat snakes. Black snakes in Australia (Pseudechis) are related to cobras, and they include snakes that are brown, including the king brown snake, which is brown in color, but not actually a brown snake. Even oddly-specific things like “centipede eater” might refer to Scolecophis or Aparallactus.

There might be more than one common name per genus, like with king snakes and milk snakes, which are both in Lampropeltis, or gopher snakes, bullsnakes and pine snakes, which are all Pituophis, or indigo snakes and cribos, which are all Drymarchon. On the other hand you can have more than one genus for a single common name, like with rattlesnakes (Crotalus and Sistrurus), mussuranas (Clelia and Boiruna), or vine snakes (Oxybelis and Ahaetulla).

Not all common names are created equal

Some common names are better than others. In the US, most species have standard common names, and there’s a reference — published by The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles (SSAR) — that lists “official” common names: a freely-available download with the comically verbose title Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in our Understanding, Eighth Edition.

Okay, okay, you win. How do we clean up this mess?

Scientific names are much more precise. They enable us to be clear about exactly which animal we’re talking about, while the only thing clear about common names is that they aren’t so clear. There are more than 3,700 species of snakes, and a surprising number of those don’t even have well-established, unambiguous common names, at least not in your language, so in many cases, scientific names are the only way to refer to a species.

(Note: Scientific names are not necessarily Latin names; they are usually Latin, but not always.)

You are already using scientific names

You might already be using scientific names without realizing it. Names like Gorilla, Hippopotamus, Chameleon, Iguana and Octopus are actually the genus names of those animals. The same with Alligator, Bison, Gecko, Hyena, Chinchilla, Rhinoceros, Llama, and a bunch of others. Other animals have common names that are very close to their genus names: gerbils (Gerbillus), rats (Rattus), and giraffes (Giraffa). Among snakes, both Boa and Python are genus names.

If you know any dinosaurs by name — Tyrannosaurus rex, Stegosaurus, Triceratops — all of those are scientific names. And you probably also know bacteria like Salmonella, Staphylococcus (“staph for short), E. coli (the abbreviation of Escherichia coli) and viruses like Ebola, Hepatitis, Rabies, Distemper and Influenza.

Nearly everyone has heard of the scientific name of our own species, Homo sapiens.

A quick taxonomy refresher

In biology, taxonomy is the science of classifying and naming groups of organisms. Together with phylogeny (evolutionary relationships) and systematics (diversification over time), it is our effort to organize living things according to their shared characteristics and relationships to one another.

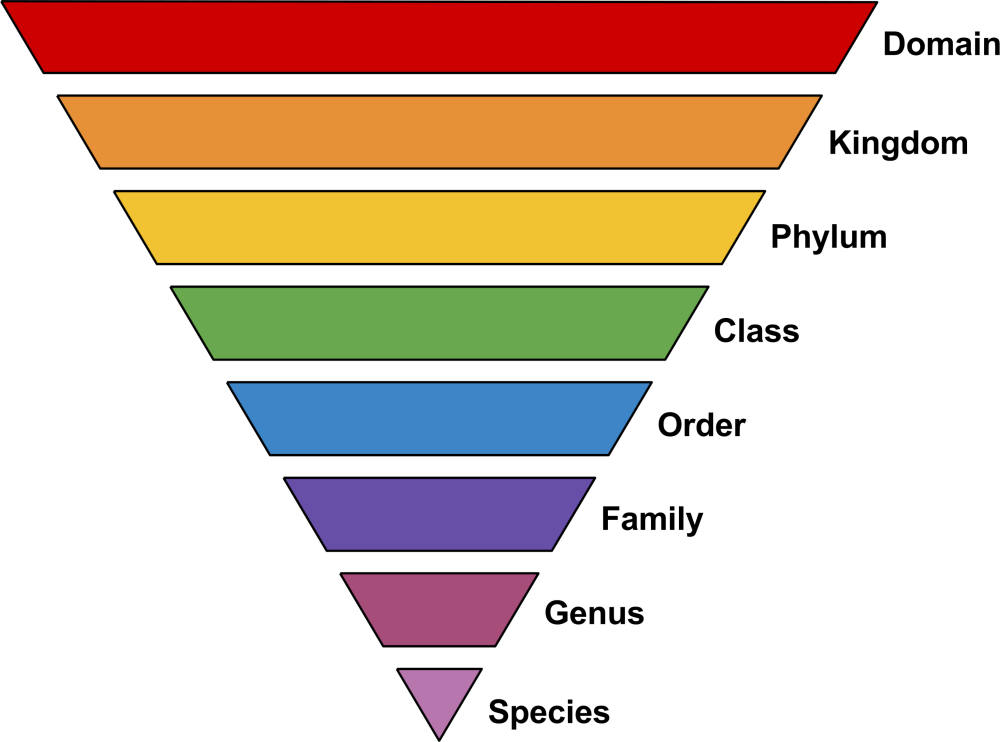

Biological taxonomy is a hierarchical system, the current principal ranks (in zoology) being:

These ranks may be aggregated into ranks like superorder or superfamily, or subdivided into ranks like subfamily, infraorder, or clade.

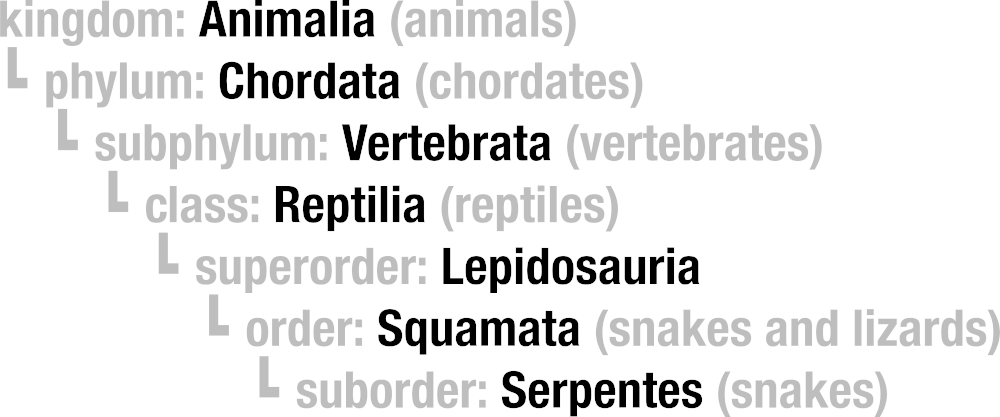

All snakes are in the order Squamata, which also includes lizards and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), and more precisely, in the suborder Serpentes:

Within the suborder Serpentes, there are (presently) 19 families: Acrochordidae, Aniliidae, Anomochilidae, Boidae, Bolyeriidae, Colubridae, Cylindrophiidae, Elapidae, Homalopsidae, Lamprophiidae, Loxocemidae, Pareidae, Pythonidae, Tropidophiidae, Uropeltidae, Viperidae, Xenodermidae, Xenopeltidae, Xenophidiidae.

Colubridae is the huge family of “typical” snakes, which includes about half of all species. Most colubrids are harmless, but a few are medically important to humans.

You’re probably familiar with some of the elapids (family Elapidae), which include mambas, cobras, sea snakes and coral snakes. You’ll also recognize some of the family Viperidae, which contains the subfamilies Viperinae (true vipers, like gaboon vipers and sawscaled vipers) and Crotalinae (pitvipers, like rattlesnakes and cottonmouths).

At the species level, organisms are known by two-part binomial names, the first part being the genus to which the species belongs, and the second part being the specific name or the specific epithet. So, for example, an eastern diamondback rattlesnake is known as Crotalus adamanteus and ring-necked snakes are Diadophis punctatus.

San Bernardino ringneck snake (Diadophis punctatus modestus). Photo by Mark Herr

Some species are further divided into subspecies, so ring-necked snakes are further divided into:

D. p. acricus — Key ring-necked snake

D. p. amabilis — Pacific ring-necked snake

D. p. anthonyi — Todos Santos Island ring-necked snake

D. p. arnyi — prairie ring-necked snake

D. p. dugesii — Dugès’ ring-necked snake

D. p. edwardsii — northern ring-necked snake

D. p. modestus — San Bernardino ring-necked snake

D. p. occidentalis — northwestern ring-necked snake

D. p. pulchellus — coralbelly ring-necked snake

D. p. punctatus — southern ring-necked snake

D. p. regalis — regal ring-necked snake

D. p. similis — San Diego ring-necked snake

D. p. stictogenys — Mississippi ring-necked snake

D. p. vandenburgii — Monterey ring-necked snake

Taxonomic organization reflects how closely-related different species are. For example, North American garter snakes (Thamnophis) and African garter snakes (Elapsoidea) are separated by 50 million years of evolution, a similar amount of time that separates cats and dogs. They share a common name, but are in completely different families and are not closely related.

Their positions in the taxonomic hierarchy, and the relationships they represent, help answer questions like, “Can this species reproduce with that species?” Different subspecies (under a single species) can often interbreed quite easily. Two species within the same genus — prairie rattlesnakes (Crotalus viridis) and Mohave rattlesnakes (Crotalus scutulatus), for example — may also hybridize, and sometimes this even happens in wild populations.

Beyond that, hybridization becomes pretty rare. Some closely-related genera, like Lampropeltis and Pantherophis may occasionally be made to reproduce together, but this is not something that normally happens, and it’s not usually possible. Hybridization across families doesn’t happen, so legends of black mambas (family Elapidae) hybridizing with black racers (family Colubridae) are pure fiction, as are claims of boas reproducing with lancehead vipers (a popular myth in Central America). Those pairings aren’t biologically possible.

Scientific names change sometimes

As we learn more about different species, their relationships to each other become more clear, and from time to time, their scientific names change. Taxonomy from 100 years ago is barely recognizable, and the methods by which relationships are inferred also changes.

Species that were once grouped by geography and morphology are now being re-examined based on DNA. Milk snakes (Lampropeltis triangulum), parrot snakes (Leptophis), cat-eyed snakes (Leptodeira), coral snakes (Micrurus), true cobras (Naja), king cobras (Ophiophagus hannah) and more are all presently under revision or have recently been revised. Eastern indigo snakes (Drymarchon couperi) were split into D. couperi and D. kolpobasileus, but that’s not yet universally accepted. Liophis were merged into Erythrolamprus. Pseustes is now Phrynonax — quite possibly the worst genus name in all of herpetology. (It sounds like a badly named medication: “Ask your doctor whether Phrynonax is right for you!”)

The “boa constrictors” in Mexico and Central America used to be the species Boa constrictor, but are now Boa imperator, but they’re still commonly called “boa constrictors,” which is now the scientific name of a different species from a different region.

Eyelash viper (Bothriechis_schlegelii). Photo by Geoff Gallice

When the scientific name for a species changes, the old names by which it was previously known become synonyms. For example, eyelash vipers, known as Bothriechis schlegelii since 1989, have the following historical synonyms:

Trigonocephalus schlegelii (Hoge, 1966)

Bothrops schlegeli (Hoge, 1966)

Bothrops supraciliaris (Stuart, 1963)

Bothrops schlegeli supraciliaris (Duellman & Berg, 1962)

Bothrops schlegelii supraciliaris (Taylor, 1954)

Bothrops schlegelii schlegelii (Taylor, 1954)

Bothriechis schlegelii (Cuesta Terron, 1930)

Trimeresurus schlegelii (Mocquard, 1909)

Lachesis schlegeli (Boettger, 1898)

Thanatophis colgadora (Garcia, 1896)

Lachesis schlegelii (Boulenger, 1896)

Lachesis nitida (Günther, 1895)

Bothriechis schlegeli (Günther, 1895)

Thanatos torvus (Posada Arango, 1889)

Thanatos schlegelii (Posada Arango, 1889)

Thanatophis torvus (Posada Arango, 1889)

Thanatophis schlegelii (Posada Arango, 1889)

Bothrops schlegelii (Jan & Sordelli, 1875)

Teleuraspis schlegelii (Cope, 1871)

Teleuraspis nitida (Cope, 1871)

Teleuraspis nigroadspersus (Cope, 1871)

Bothrops (Teleuraspis) nigroadspersus (Steindachner, 1870)

Bothrops schlegeli (Jan, 1863)

Teleuraspis schlegeli (Cope, 1860)

Lachesis nitidus (Günther, 1859)

Trigonocephalus schlegelii (Berthold, 1846)

These changes reflect how understanding of the species (and its relationships to other species) develops over time and, to some degree, how herpetologists battle it out over how best to classify it.

The bottom line

Scientific names reduce confusion. You may think they suck, but they suck far less than common names, and they’re really not that hard to learn.

Special thanks to Andrew Durso, Bridgette Gigi, and Tony Daly-Crews, whose suggestions help turn this brain-dump into something more like an article.